Some Heroes Wear Clogs

Written by Annie Tressler / Illustrated by David Rey

As a patient who has navigated the labyrinthian United States healthcare system for most of my adult life, it’s often hard to imagine it as anything but abhorrent. Yet I’m working on seeing the world through rosier glasses (wish me luck), and, sometimes, there are pockets of wonder that creep through even the most opaque bureaucratic nonsense. In my case, it came in the form of a nurse specializing in diseases having to do with shit.

Throughout my 20s, I was lucky to have health insurance through my job. It carried me through flares of my Crohn’s disease, as well as surgeries where my guts were extracted and diseased parts excised, then tossed unceremoniously into medical waste bins.

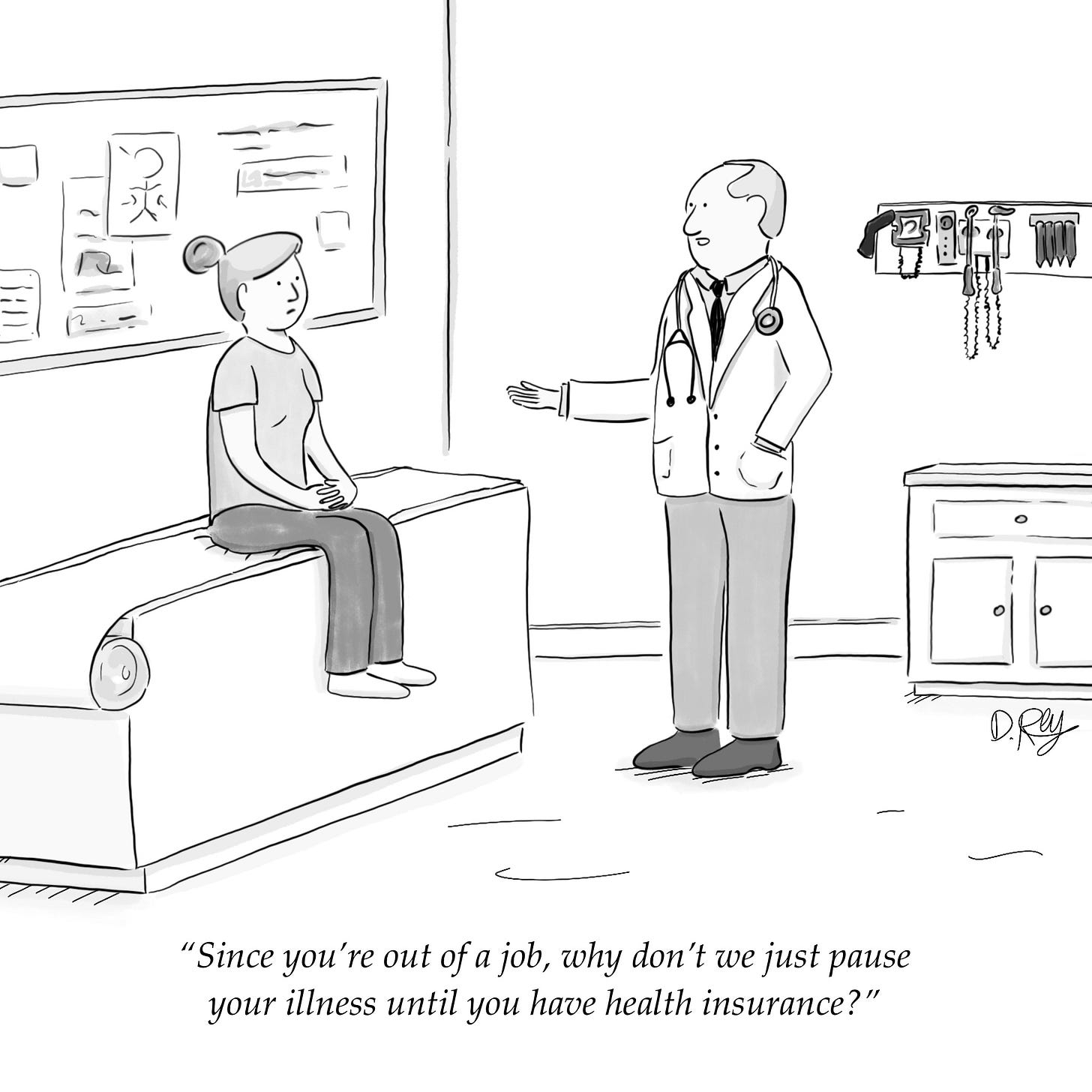

And then I didn’t have a job. And I didn’t have insurance. With a chronic illness.

I found myself, in a word, fucked.

As we know, illness is a living thing. Like an irascible toddler, it needs structure: “milk” (or medicine), attention, a militaristic schedule. It does not care whether your insurance is active, terminated, or somewhere in between.

When insured, I paid five dollars for my Stelara syringe with the help of a financial assistance program.

The street price? $30,000. Not having that on hand, I embarked on a Sisyphean task to get the syringe and shut that Crohn’s baby up any way I could.

Like many patients on biologics, I had a short window before my Stelara risked becoming null and void; a gap in treatment could allow my immune system to soldier up and create antibodies, rendering it useless.

How would I get my syringe? Beg, borrow, lie, steal?

I cried, cursed the system, then hauled my uninsured self to my doctor’s office to see where desperation, moxie, and persistence might get me. I call this skill “benevolent Karening.”

I sat in the room, explaining my situation to the nurse. Angelic, she handed me tissues, and miraculously, my syringe. “We’ll figure it out,” she said, mentioning how doctors can sometimes offer samples in emergencies. Her kindness and professionalism, and this simple act of care reminded me that there’s still something human in the system.

It’s not the bureaucrats in suits who should be recognized but the ones in clogs, on the ground, injecting the medicine, listening to innumerable amounts of pain, worry and woe — those who are doing the actual caretaking.

I shot myself up, wiped my snot, and remain—miraculously, stubbornly—in remission. (And now, insured.)

This was written by Annie Tressler and illustrated by David Rey.